Building a High-Efficiency Tokenizer for Telugu LLMs

In the world of Large Language Models (LLMs), we often talk about parameters, FLOPS, and datasets. But there is a silent gatekeeper that determines how well a model "understands" a language even before the first neuron fires: The Tokenizer.

As we embark on training a foundational LLM from scratch specifically for the Telugu language, we quickly realized that standard off-the-shelf solutions wouldn't cut it. Today, we’re diving deep into why tokenization matters, why we built a custom solution, and how our new Telugu-specific BPE tokenizer is outperforming GPT-4’s efficiency by over 70%.

What is Tokenization?

Before an LLM can process text, it must convert words and sentences into numbers (tokens). Think of it as breaking a Lego castle down into its individual bricks so the computer can understand the structure.

Common Tokenization Options:

- Character-level: Breaking text into individual letters. It’s simple but results in very long sequences, making it computationally expensive.

- Word-level: Assigning a unique ID to every word. This fails with large vocabularies and "out-of-vocabulary" words (e.g., new slang or technical terms).

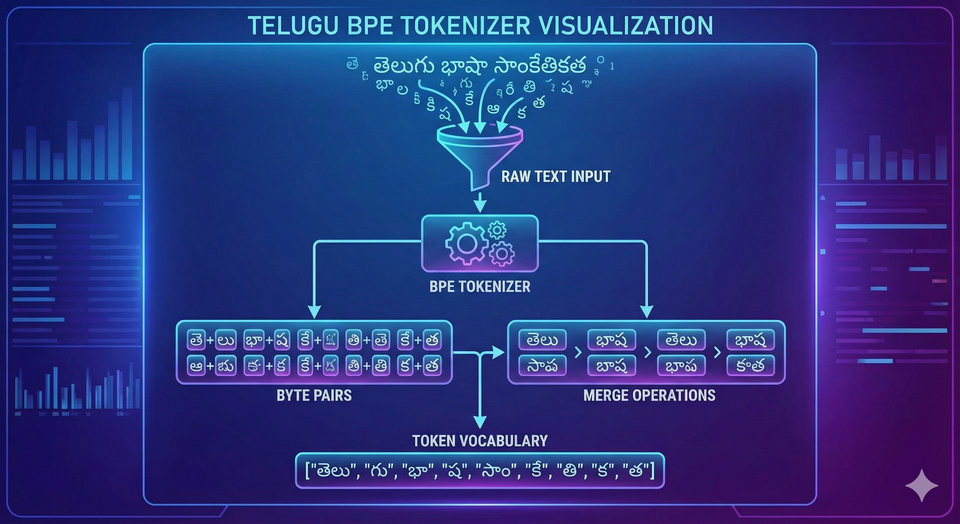

- Subword-level (BPE/WordPiece): The "Goldilocks" zone. It breaks common words into whole pieces and rare words into smaller sub-units. Byte Pair Encoding (BPE) is the industry standard used by GPT-3 and GPT-4.

Why "Telugu-First" Needs a New Tokenizer

Most global LLMs (like GPT-4 or Llama) are trained primarily on English data. Their tokenizers are optimized for the Latin alphabet. When these tokenizers encounter Telugu script, they struggle.

The "Telugu Tax": In a standard English-centric tokenizer, a single Telugu character—which is visually complex—might be broken down into 3 or 4 different tokens. This means:

- Higher Costs: You pay for more tokens to say the same thing.

- Smaller Context: The model "forgets" faster because its memory (context window) is filled up with fragmented sub-tokens.

- Poorer Performance: The model struggles to learn the semantic meaning of fragmented scripts.

To solve this, we built a Rust-based BPE tokenizer trained exclusively on a massive corpus of 60 billion Telugu characters.

Our Architecture: Rust + Tiktoken

For our implementation, we combined the safety and speed of Rust with the inference efficiency of Tiktoken.

- Training (RustBPE): We used a custom Rust implementation to handle parallel training. Training on 60 billion characters is no small feat, but our pipeline completed the process in just ~41 minutes.

- Inference (Tiktoken): For the model to run fast in production, we utilized the GPT-4 style Tiktoken library, ensuring low latency during text generation.

- Pre-tokenization: We use a custom regex pattern to split text intelligently before applying BPE merges, preventing the tokenizer from accidentally merging numbers with words or punctuation.

Technical Specifications:

| Parameter | Value |

| Vocab Size | 65,536 (2¹⁶ tokens) |

| Max Chars Processed | 60 Billion |

| Mean Token Bytes | 7.76 |

| Special Tokens | 9 (e.g., `< |

Performance: Crushing the Competition

The results of our evaluation were even better than expected. We compared our tokenizer against GPT-2 and GPT-4 across various domains like news, literature, and even code.

The "Efficiency Ratio" Comparison

The "Ratio" below represents Bytes per Token. A higher ratio means the tokenizer is packing more information into a single token (higher efficiency).

Comparison with GPT-4

| Text Type | GPT-4 Ratio | Ours Ratio | Efficiency Gain |

| Telugu News | 1.56 | 5.66 | +72.4% |

| Telugu Literature | 1.57 | 5.47 | +71.3% |

| Telugu Poetry | 1.57 | 5.66 | +72.3% |

| Telugu Code | 1.72 | 4.41 | +60.9% |

On average, our tokenizer achieved a 70-82% reduction in token count. This means that for the same "cost" or "memory space," our model can "read" or "write" 5 to 6 times more Telugu text than GPT-4.

The Road Ahead: Research Ideas for New Tokenizers

While BPE is the current king, the field is evolving. If you are looking to push the boundaries of tokenization, here are a few research directions:

- Morphology-Aware Tokenization: Instead of purely statistical BPE, can we build tokenizers that understand Telugu grammar (Sandhi and Samasa) to split words at linguistically meaningful boundaries?

- Visual Tokenization: Moving away from text entirely and treating characters as images (pixels) to bypass the "encoding" problem altogether.

- Dynamic Vocabulary: A tokenizer that adapts its vocabulary based on the domain (e.g., switching between a "Medical Telugu" vocab and a "Legal Telugu" vocab) to maximize compression.

- Optimal Byte-to-Token Ratios: Researching the mathematical "sweet spot" between vocabulary size and model depth—does a larger vocabulary always lead to a smarter model, or is there a point of diminishing returns?

Conclusion

Building a tokenizer isn't just a preprocessing step; it's the foundation of linguistic parity in AI. By building a custom, Telugu-centric tokenizer, we’ve effectively increased our model's efficiency by 5x before even starting the training process.

Stay tuned as we move into the next phase: Training the weights!